As ‘East India Company’ was coiling a massive debt to the government for funding its military expansion in India, something was needed to be done. They needed to find a traceable good other than silver, that the Chinese would want to import, to offset the massive costs of the Victorian need for tea. The answer to their concern was being used in the East Indies (Probably Java) and it was nothing but a mixture of ‘Tobacco and Opium’.

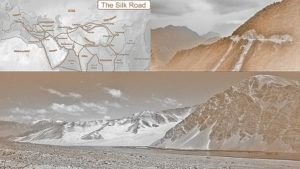

‘Opium’ was well known to the Greeks (Thanks to Hippocrates) and Romans (Thanks to Galen) as a powerful pain reliever. It was also used to induce sleep and for purgation. It was even thought to protect the user from being poisoned, along with supplementary effects of pleasure as a bonus (If Not Abused). ‘Opium’ was first introduced to China by the Turkish and Arab traders in the late 6th or early 7th century. The trading and production of ‘Opium’ spread from the Mediterranean to China by the 15th century and by 17th century it was in limited use, mostly for medical purposes. In the 1700s the Dutch introduced the practice of smoking the mixture of ‘Opium and Tobacco’, using a pipe, which they had learned in North America. The Chinese usually traded Silver for the ‘Opium’. By then the addictiveness of ‘Opium’ had already been known to the ‘Yongzheng Emperor’ of China. By 1729 it had become such a problem that the ‘Yongzheng Emperor’ prohibited the sale and smoking of ‘Opium’. However, law failed to enforce it. In 1796 the Jiaqing emperor outlawed ‘Opium Importation’ and cultivation which proved to be equally unsuccessful. ‘Opium’ became one of the products traded along the famed Silk Road, which is the 18th-century term for a series of interconnected routes that ran from Europe to China. These trade routes developed between the empires of Persia and Syria on the Mediterranean coast and the Indian kingdoms of the East. By the late Middle Ages the routes extended from Italy to China and to Scandinavia. The unofficial trade of ‘Opium’ continued to flourish.

According to the import data, by the early 1800s tea-trade figures were unimaginably high in England. An average English household spent about 5% of their income, on tea purchases. The government itself was basically propped up by the tea-trade because it lent the company, the required money to invest and conquer certain parts of India. A huge portion of East India Company’s revenue came from transporting tea from China. They were even more dependent on the tea-trade as that revenue was being used to repay the debt against the expenses that the company had incurred. By 1767 British government had intervened in certain affairs of India and the company had to settle the mess for 10% of annual plunder or 4 million pounds annually, in exchange for extended support. As the craze for tea was consuming England, the company realised that regardless of their monopoly, their conquests in India weren’t ensuring as much returns, as they had expected, mostly due to rampant corruption among their own hierarchy. The corruption among their ranks went to such an extent that during 1787 to 1795 British government impeached the infamous Governor-General of Bengal – Warren Hastings, for grave misconduct in dealing with business propositions. This way, while the employees of the company were getting richer and richer, eating on the company’s profit, pressure on creating new demand for existing supply was becoming a necessity for the company’s survival in the South-East Asia. Their plans to grow cotton in India too had gone awry, as cotton production in America and especially in Egypt were on the rise and the demand to price ratio was no longer a feasible consideration for the company. Even after carefully manoeuvring towards a dual system of governance in India, the company struggled to keep afloat under the massive debt. Since necessity needs to find a solution, the company decided to grow ‘Poppy’ in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. It was about to become a compulsion for the people of India and a rescuer for the company. They already had a system in place that guaranteed inexpensive production and transportation of commodities. Overnight huge tracts of agricultural land in the Bengal-Presidency were transformed into rolling ‘Poppy-Fields’, and while the native farmers lamented the death of golden harvests, the British kept raking on the opportunity. Company civil servants fanned out into the western areas of Bengal, into Bihar and Orissa, draining a once-thriving agricultural economy into aridness. Now all the Company aimed to do is to extract ‘Opium’ and find a way to sell it, in order to meet the ravening demands in China, however with only one minor problem. ‘Opium was illegal in China’.

So they basically set up a market in Calcutta, the part of India that was closest to China and the one they controlled, and let the customers find them, after which, they would let the smugglers take care of the rest. So now you’ve got a bunch of dodgy characters selling drugs in the middle kingdom, basically backed by the largest corporation and the largest national economy of the world. As the Indian ‘Opium’ was known to be stronger than the domestically grown alternative, the prices hiked, consequently shooting up the sale of ‘India-Grown Opium’ in China. By 1835 roughly 3 million 64 thousand pounds of ‘Opium’ was sent to China and that number grew bigger when in 1833 the British government decided to do away with the Company’s monopoly on the ‘Opium-Trade’, which they did, resulting in the supply of ‘Opium’ becoming unregulated. As supply grew, driving the prices down, the substance became more accessible to the customers. By 1839 nearly 5 million 639 thousand pounds of ‘Opium’ was pouring into China every year.

But as one can assume, the Chinese weren’t beating around the bush, while all this was happening. To take a hint of the money that was flowing out of the country, the emperor appointed ‘Lin Zexu’ as a Canton Commissioner with full authority to give all orders that might be deemed necessary to eradicate the ‘Opium-Trafficking’ forever. Although he was known as an honest, old fashioned and well-informed official, he was unaware of the British involvement in the Napoleonic wars (1803 – 1815) and initially did not see them as a viable threat. On top of it, he tried to reject the appointment as he felt he was entering into a trap. By March of 1839 he reached Canton. It was the entrance route of all the ‘Opium’, so he planned to uproot its sources. His actions were swift and uncompromising. He arrested thousands of Chinese ‘Opium Traders’, forced addicts into rehabilitation centres, confiscated utensils and closed the dens of the illegal substance. Then he took-on the western traders and by July 1839 Lin had arrested about 1700 native offenders, confiscated 44,000 pounds of ‘Opium’ and over 70,000 ‘Opium-Pipes’.

At first he wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria appealing to her conscience, where he reportedly wrote the following lines – “The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians. By what right do they then in return use the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? Where is your conscience?” It was a letter that she ‘most likely’ never received. When Lin did not get the reply that he had demanded, he forced the so called ‘foreigners’ to submit their warehouses to the authorities. In reply the foreign merchants stalled and evaded by giving up small amounts of their ‘Opium’ stock. However, it was nowhere near what Lin Zixu had expected. So he marshalled the troops and seized all the warehouses. The merchants held up for about a month and a half, eventually giving in, and were forced to surrender 21000 chests of ‘Opium’. For the next 23 days Zexu burned the ‘Opium’, using Lye. This was probably the King’s-Ransom against the profit amount of illegal ‘Opium-Trade’.

Now there is some debate over whether the Chinese even offered anything in exchange for the surrendered ‘Opium’, but what is certain that the merchants never received any tea and instead the local chief superintendent of British trade, Captain Charles Elliott promised the merchants, that the British Government would cover their losses, once they leave peacefully, which of course the British Government absolutely refused to do. The outcry over this illegal siege of British goods began to grow in England.

Meanwhile in China a reprehensible incident happened where a few drunken British sailors had beaten a Chinese citizen to death. Lin Zixu demanded the execution of a British Sailor in recompense. Captain Elliott who actually disliked the ‘Opium Trade’ and was somewhat sympathetic to the situation in China, declared rewards for evidence against the persons who had committed the murder and gave money to the victim’s family. He then had the criminals tried on his ship, inviting Lin Zexu or a representative to witness the procedure. Although none took to the invitation, he sentenced the men to hard labour back in England.

Despite his efforts, his relations didn’t work with Lin Zexu. After all, the whole point of Lin Zexu’s demand was to show that the foreigners weren’t allowed to violate the Chinese ‘Law of the Land’. In response he stopped the food supplied to the British and posted signs telling them that the water sources had been poisoned. Next he ordered the Portuguese to eject all of British from Macau. He was going to see British merchants and their drugs, off Chinese soil once and for all.

So the British had to retreat to a barren island off the coast, that would eventually be known as Hong Kong. They had to deal with the crisis (Especially Related to Food). Captain Elliott sent a request for food, to which the reply was delayed and so he sent his men ashore to buy some food. But as they were heading back, these provisions were seized back by Chinese officials.

Soon a fight broke out between the blockading Chinese and the British, and thus on September 4th 1839 began the first ‘Opium War’.

Featured image courtesy: pxhere.com

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia (Wikimedia: Creative Commons)